Don't you hate it when this happens? You find a great old photo from your grandmother's collection; itchy with anticipation, you flip it over, hoping to find some enlightening runes there. Alas, you see only the cryptic phrase, "Me and Papa in front of the house."

Whaaa? Who is "Me?" Who is "Papa?" What house? Where? When? Sigh. It's almost more frustrating than finding nothing on the back, because there was just that microsecond there when you saw writing and...sigh.

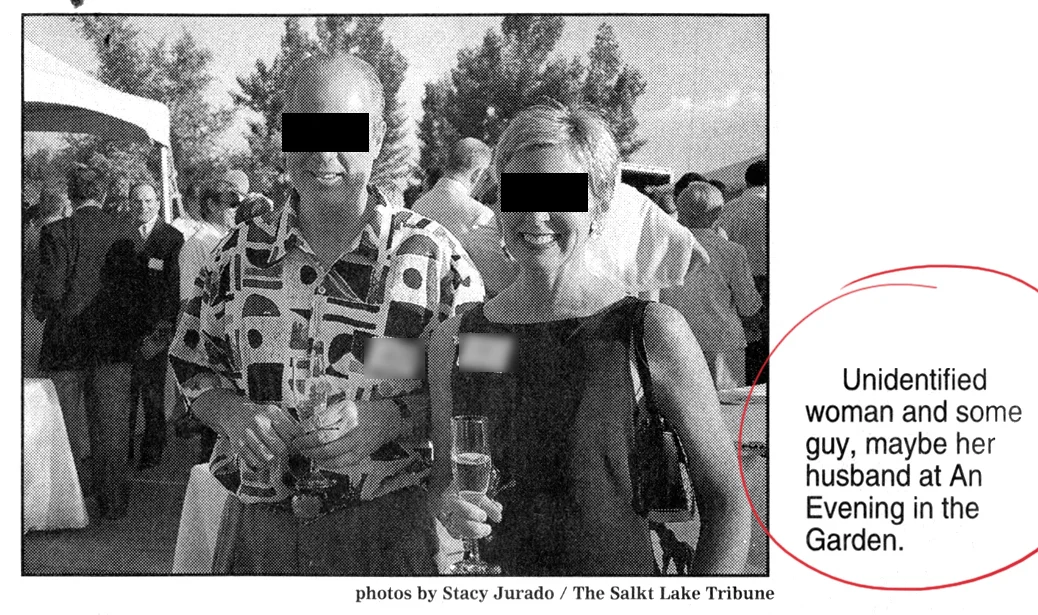

Lest you think only amateurs neglect photo identification: even so-called professionals sometimes get away with caption murder. I stumbled across the newspaper photo below while scanning something for a client. This was actually printed in an actual medium-sized city newspaper. "Unidentified woman and some guy, maybe her husband." Uuum...

Not a good caption: "Unidentified woman and some guy, maybe her husband." (I won't even call your attention to the typo in the photo attribution or the lack of a comma after "husband.") I blacked out the faces just in case these people want to remain unidentified, or if it isn't her husband after all.

So, how do I write a good caption for a photo in my family history book?

The caption should clearly identify the subject(s) and other important information in the photo, without detailing the obvious. It establishes the photo's relationship to the text, and serves to draw the reader further into the story. Captions can be short, or they can contain longer material, descriptions, or even a mini-story.

1. Be specific, but not overly so.

This is the first photo in the book, so the caption contains the full name and date to introduce the subject. Subsequent photos of the subject in the book use only his first name, since the book is about him.

For instance, if you are writing a book about Mortimer Brewster, you don't necessarily have to include "Mortimer Brewster at the beach" or "Mortimer Brewster at his home in Brooklyn, New York" under each and every photo; the first name is probably sufficient. If you know the year the photo was taken, it maybe helpful to add it, or you can add "circa 1942" (or "c. 1942" or "about 1942") if you don't know the exact date but want to approximate it.

Think about who might be reading your book not just next year, but a hundred years from now. Will they know who "Teddy" is and how he relates to Mortimer? Make sure to leave enough clues for your reader to understand the relationships.

2. It's okay if the caption is humorous or tells a story of its own.

Keep in mind that many people will pick up your book and scan the photos and captions first. Interesting captions can help draw the reader into the rest of the narrative, or at least give them the gist of it if they don't have time to read the whole thing.

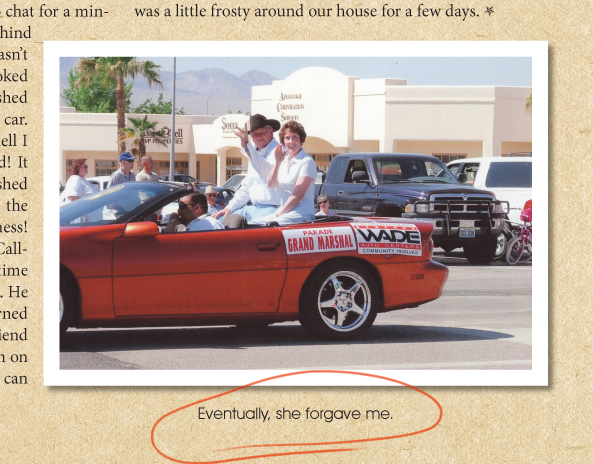

This caption imparts information in a humorous way.

"Eventually she forgave me." Cryptic, but effective at drawing the reader into the story to find out more. The subjects of the photo are also the subjects of the book, so identifying them in this case seems redundant. Additional details are in the adjacent story.

3. Make sure the caption is readable.

When choosing a typeface for your caption, make sure it is easy to read and different in some way from the main body of your text. If you use a serif font for your body text, consider using a sans-serif font for your caption. Or make it a little smaller or bolder than the body text.

The above font has a nice old-fashioned feel, but it is a little too fussy for a small-print caption. Save fancy fonts for title pages and short pieces of text. But make sure the caption type doesn't blend in too much with the type in the main narrative, or it could get confusing.

The above caption uses a very different typeface and color to differentiate it from the main body text. There is also sufficient white space between the caption and the body text.

Do you always need to caption every photo? Not necessarily; some stand on their own or the subject is obvious. But when it doubt, caption it. Your reader will thank you.